The Traveling Mathematician: How Geometry Once Hit the Road on a Donkey

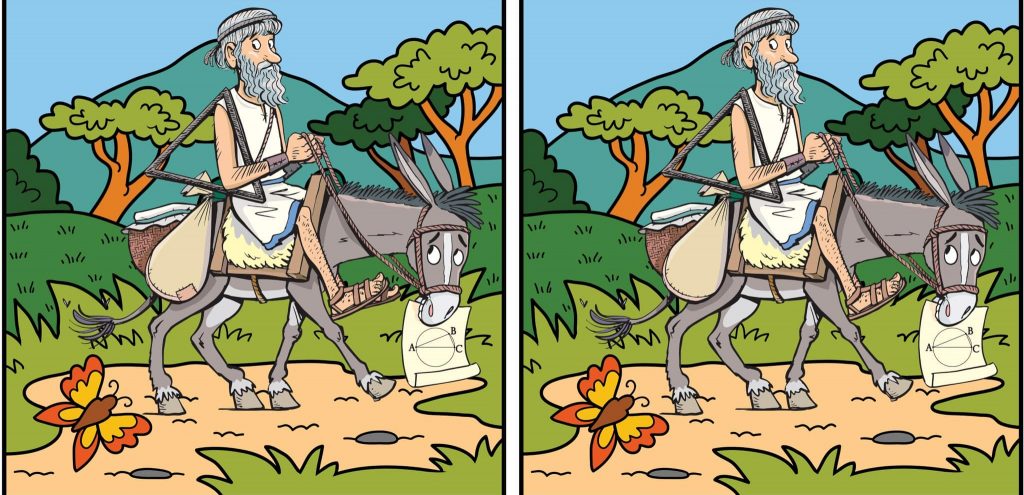

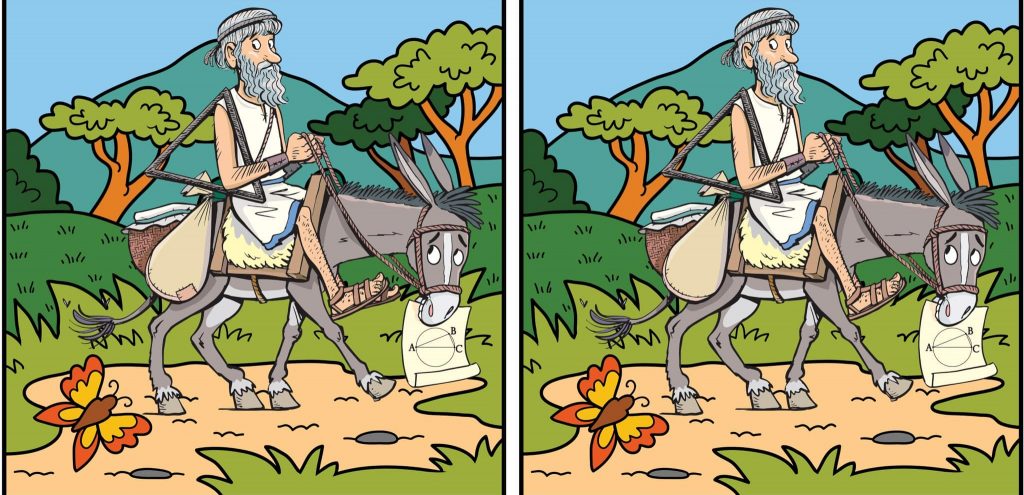

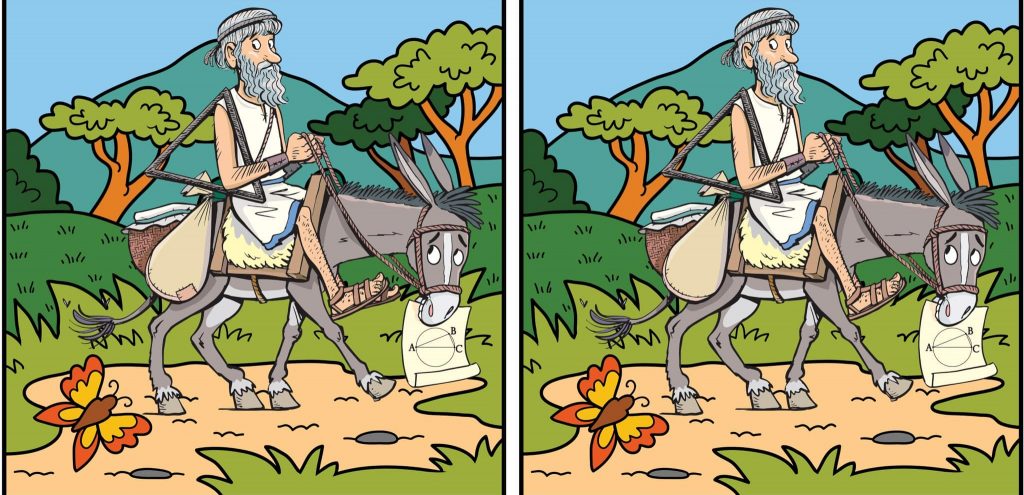

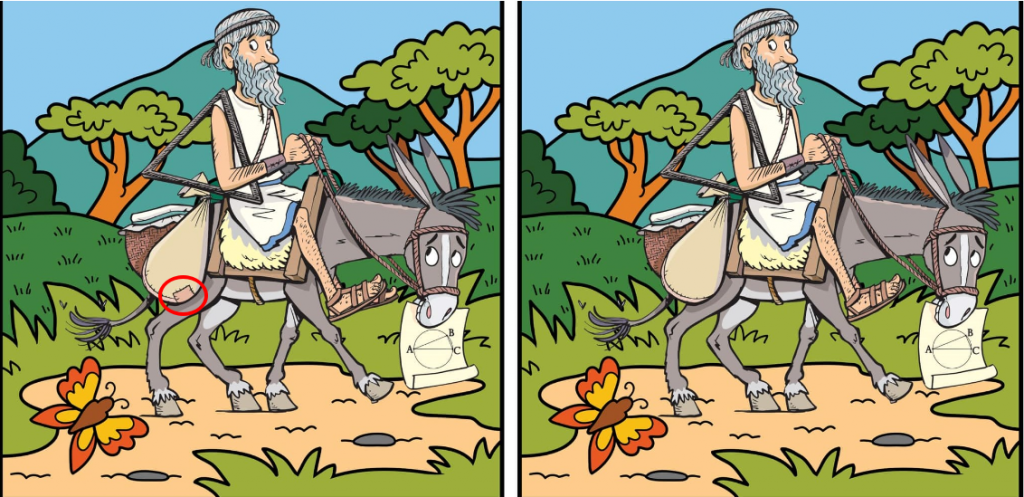

When you think of geometry, you probably picture chalkboards, rulers, and sleek lecture halls. But long before modern classrooms existed, the great minds of mathematics packed up their scrolls, strapped on their tools, and hit the dusty roads—often atop humble donkeys. This vivid scene of an elderly scholar guiding his donkey through rolling hills, with a geometry diagram in tow, brings to life a fascinating chapter in intellectual history: the age of the traveling mathematician. Let’s embark on that journey together!

Geometry on the Move: A Mobile Classroom

In an era without printed textbooks or digital projectors, knowledge traveled at the speed of a walking mount. Renowned figures like Euclid’s successors and Pythagorean followers carried papyrus scrolls and wooden compasses strapped to their saddles. Imagine a portable classroom: a sturdy triangle ruler slung over one shoulder, rolls of diagrams dangling by leather cords, and a curious donkey serving as both transport and silent companion.

This mobile approach had unexpected perks. Instead of confining lessons to a single city-state, math teachers could reach remote villages, trade routes, and seaside ports. Local youth gathered on sunbaked paths to watch demonstrations: inscribing perfect circles in the dust, measuring angles with wooden set squares, and proving theorems by simple construction.

Bridging Cultures: Mathematics as a Universal Language

As our scholar traversed olive groves and mountain passes, geometry became a bridge between diverse peoples. The symbols on his scroll—a triangle labeled A, B, C—meant the same thing whether he stopped at an Egyptian caravanserai or a Greek polis. Numbers and shapes spoke louder than words, sparking dialogues where language barriers existed.

In exchange for sharing geometric methods (like bisecting angles or calculating areas), travelers often received local insights: Babylonian sexagesimal arithmetic or Indian approximations of π. The donkey thus carried not only Euclidean postulates but also the seeds of global mathematical collaboration.

Tools of the Trade: From Compass to Scroll

What did our itinerant mathematician pack in his saddlebag? Let’s peek inside:

- Wooden Compass and Divider: For drawing circles in sand or on parchment.

- Set Square: A rigid right-angled triangle—essential for right‐angle constructions.

- Papyrus Scrolls: Handwritten proofs and diagram templates, rolled up and secured.

- Stylus & Inkpot: To jot down fresh discoveries or correct errors.

- Measuring Cord: Knotted at equal intervals, doubling as a rope for donkey care.

Each tool was both simple and ingenious, empowering concept demonstrations without walls or wheels—just keen eyes and deft hands.

Lessons in the Open Air: Teaching on the Go

Picture a roadside clearing under a lone olive tree. The mathematician unrolls a scroll depicting a circle with chord AB and C, and invites villagers to mark points in the sand. He teaches them that the line from the circle’s center bisects the chord at right angle, using sticks and pebbles to illustrate every step.

This hands-on approach grounded abstract ideas in tangible experience. Without parchment constraints, students could trace larger diagrams—big enough for an entire group to inspect at once. The donkey, nibbling nearby grasses, waited patiently while the theorem unfolded under the azure sky.

Challenges on the Path: Trials of a Roaming Scholar

Life on the road wasn’t all proofs and palm fronds. Our traveling teacher faced real hurdles:

- Weather Woes: Rain could wash away diagrams in the dirt, and high winds might tangle scrolls mid-lecture.

- Donkey Dilemmas: A stubborn mule could balk at steep inclines or bolt when spooked by a startled camel.

- Supply Shortages: Running low on ink or papyrus forced impromptu lessons in pure oral tradition.

- Political Roadblocks: City-states sometimes prohibited foreign teachers, fearing intellectual “invasion.”

Yet these obstacles sharpened resilience and adaptability—qualities mirrored in the flexible reasoning that geometry itself demands.

Legacy on Four Hooves: Donkey-Driven Discoveries

Though ancient roads have long since given way to paved highways, the spirit of wanderlust in scholarship endures. Our donkey-riding mathematician reminds us that real learning thrives outside formal walls. By carrying geometry to new frontiers, these early teachers seeded ideas that blossomed across continents.

Today’s educators can draw inspiration from their legacy: take lessons outdoors, embrace cross-cultural exchange, and remember that even the humblest tools—a stick, a scroll, or yes, a patient donkey—can unlock big ideas.

Conclusion

Before the digital age, geometry lectures rolled into town on four hooves, guided by determined scholars armed with compasses and set squares. These traveling mathematicians bridged cultures, taught under open skies, and proved that knowledge, like a trusted donkey, thrives on the journey. So next time you study angles or draw circles, imagine the wind in ancient scrolls and the steady clop of hooves—because true discovery often begins when we step beyond the classroom and walk the road less traveled.